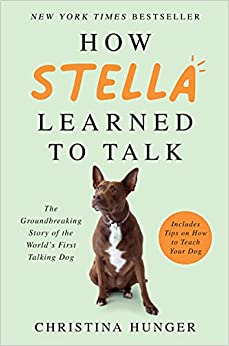

AAC (Augmentative and Alternative Communication) devices are commonly used to help children with speech disorders communicate, and a tool that speech therapist Christina Hunger often uses. But it wasn’t until she adopted her dog Stella, a Catahoula Blue Heeler mix, that she found how impactful AAC devices could be in her personal life.

When Hunger adopted Stella, she quickly began to notice that her new dog was showing signs commonly seen in human speech development. As she says in her book, How Stella Learned To Talk, “Stella approached her dishes and pawed her water bowl… …in only two days of living here, Stella learned what each dish was for. She even gestured by pawing her dish to let me know that she needed more water. Her communication was already so clear.”

Stella continued to learn more words, and use the buttons more often. She learned when in the day each event was, saying words like “eat” only when it was the time of day when she typically ate or “beach” during the time when Hunger would take Stella to the nearby dog beach, and even noticed when these routines were disrupted, leading to her first two-word phrase, which occurred when Hunger hadn’t fed Stella yet, as they had gone to the beach first. “Eat no,” Stella said. Those words became the first of many two-word phrases.

Learn more about Stella, The World’s First Talking Dog, and how you can communicate with your dog at the Hunger For Words website.